Where the Esports Money Went in 2025

Recommended casinos

Prize money in esports does not follow talent. It follows infrastructure, institutional investment, and deliberate event strategy.

In 2025, three countries accounted for roughly half of the prize money distributed across the world's top ten host nations. Saudi Arabia, China, and the United States dominated the table, and the gap between them and the rest was not marginal. It was structural.

We reviewed Esports Charts' 2025 host-country data, which covers more than $270 million across 10,500 tournaments globally, and the findings were particularly interesting. The numbers indicate a market shaped by three forces: state-backed mega-events, publisher-controlled domestic ecosystems, and repeatable event infrastructure. Legacy esports strength still matters, but it no longer determines where the money lands. That shift is more significant than it might first appear.

The Full Ranking

Before getting into the drivers, here is where things stood at the end of 2025:

- Saudi Arabia — $39.66M

- China — $34.82M

- United States — $23.12M

- Romania — $7.79M

- France — $7.57M

- Thailand — $7.11M

- Canada — $5.28M

- Germany — $5.22M

- South Korea — $5.03M

- Japan — $4.28M

The top three countries alone accounted for nearly half of all prize money hosted among the global top ten.

The top ten combined for $139.88 million, around 52% of the global total. The top three alone accounted for roughly half of that. One point worth stating clearly before proceeding: these rankings measure where tournaments were hosted, not where the winning players came from. A Korean team winning a tournament in Riyadh adds to Saudi Arabia's total, not South Korea's. That distinction matters a lot when you are trying to understand what these numbers actually mean.

More than two-thirds of the prize money hosted by the top ten countries flowed into just three markets, underscoring increasing structural concentration.

Saudi Arabia: Buying the Calendar

Saudi Arabia, at the top of this table, is the most telling story in the whole dataset.

The country's position is almost entirely attributable to the Esports World Cup. The EWC circuit in Riyadh ran at least 25 distinct tournaments across a concentrated summer window, covering Dota 2, PUBG Mobile, Mobile Legends: Bang Bang, Honor of Kings, and several others. The headline EWC prize pool for 2025 has been reported at approximately $70 million. However, a portion of the funds flows through club programs rather than individual game tournaments, which explains why the hosted prize pool is lower than the headline number.

What we find compelling about the Saudi case is its deliberate nature. This is not a country that developed a grassroots scene and gradually attracted events. It identified esports as a strategic opportunity, directed serious state-backed capital into it, and moved fast. The result is a number one ranking that did not exist a few years ago.

The question we keep coming back to for 2026 is whether other sovereigns, particularly elsewhere in the Gulf or in Southeast Asia, try to replicate the model. The playbook is not a secret. The capital requirement is the barrier.

China: When the Publisher Is Also the League

China's $34.82 million total is built on a fundamentally different foundation and, in some respects, is the more impressive of the two leading models.

Rather than importing prestige through mega-events, China generates prize money domestically through publisher-controlled leagues that run year-round. The King Pro League is the clearest illustration. The KPL Grand Finals 2025 reportedly featured a $9.83 million prize pool for a single event in a single title. That figure alone exceeds the entire annual hosted total of South Korea, Germany, or Japan. Tencent controls the KPL format, the prize structure, and the broadcast rights. When a publisher is also the league operator, the prize pool reflects a business decision as much as a competitive one.

China also hosted LoL Worlds 2025, which Esports Charts identified as the year's most-watched esports event. This entails additional production expenditures, international media attention, and greater weight in the rankings.

The China model is actually harder to replicate than the Saudi model, precisely because it depends on having both the audience scale and the publisher infrastructure already in place. Those conditions exist in China across multiple titles simultaneously. Most markets cannot make the same claim.

The United States: Reliable but Capped

The US total of $23.12 million is not built around any single flagship event. It reflects a mature ecosystem spread across Counter-Strike (the Austin Major in Texas), Dota 2, Rainbow Six, fighting games, and various publisher-backed franchised leagues.

No single title dominates the U.S. market, which is both a strength and a constraint. Diversification means the overall number stays relatively stable even when specific games lose momentum. But it also means the US is unlikely to challenge Saudi Arabia or China at the top of this table without a structural shift. It lacks the sovereign investment of the former and the concentrated domestic publishing ecosystem of the latter.

That said, third place in a global ranking with this level of competition is not to be dismissed. The US event infrastructure, broadcast capacity, and venue network make it a consistently attractive host across a wide range of publishers and organizers. It is the safe bet in this ranking, for better and worse.

Asia and the Middle East dominate hosted prize pools in 2025, reflecting both publisher ecosystems and sovereign-backed event strategy.

The Rest of the Top 10

Romania (#4, $7.79M)

Romania is the most underappreciated story in this table. Its position near the top of a global prize pool ranking appears surprising until you consider what the country offers: reliable logistics, established operator relationships, and a track record of hosting large Counter-Strike events efficiently. PGL Bucharest 2025 contributed a $1.25 million prize pool, and Romania's overall total reflects years of quietly building that reputation. The country did not develop a domestic esports audience before attracting events. It developed hosting capability first, and the prize money followed. There is a lesson in that.

France (#5, $7.57M)

France's total is largely attributable to a single event. VALORANT Champions 2025, hosted in Paris, featured a $2.25 million prize pool, likely accounting for approximately 30% of France's annual total. Paris is a proven premium venue for esports, and Riot has used it accordingly. The caveat is that France's ranking is largely contingent on Riot's scheduling decisions. If Champions moves elsewhere in 2026, France drops down the table, and there is no obvious replacement event to fill the gap.

Thailand (#6, $7.11M)

Thailand is essentially KRAFTON's year-end hub, and the concentration numbers make that very clear. The PUBG Mobile Global Championship 2025 and the PUBG Global Championship 2025 together generated approximately $4.5 million in Bangkok, accounting for around 63% of Thailand's full-year hosted total. That is the highest single-publisher concentration among the top ten countries. Thailand's esports footprint on this leaderboard largely reflects KRAFTON's inclusion, placing it among the more structurally fragile positions in the ranking.

Canada (#7, $5.28M)

Canada's total reflects a moderate number of mid-size international tournaments across multiple titles. Public data do not disaggregate Canada's drivers with the same level of detail as the top five. Still, the figure is consistent with a market that benefits from proximity to the US, shared infrastructure, and a steady base of publisher and organizer activity. It is not a headline story, but it is a consistent one.

Germany (#8, $5.22M)

Germany's top-ten finish is anchored by one decision: Valve chose Hamburg to host The International 2025. Dota 2's global prize money totalled approximately $23.1 million in 2025, and TI accounted for roughly one-tenth of that, placing the event's prize pool at approximately $2.3 million. Add Germany's broader European circuit presence, and you get a top-ten total. Without TI, Germany is likely excluded from the list entirely. That is a significant single-event dependency and warrants monitoring if Valve rotates the host city in future years.

South Korea (#9, $5.03M) and Japan (#10, $4.28M)

Both Asian markets exhibit sustained, multi-title growth rather than single-event spikes. South Korea maintains a strong Riot ecosystem through recurring League of Legends competitions and a well-established production infrastructure. Japan's rise is arguably the more interesting trajectory of the two. Growth is being driven by Apex Legends, VALORANT, fighting games, and domestic publisher leagues, suggesting a broadening base rather than dependence on any single title. We will be watching Japan's 2026 numbers closely.

Three Patterns That Explain the Whole Table

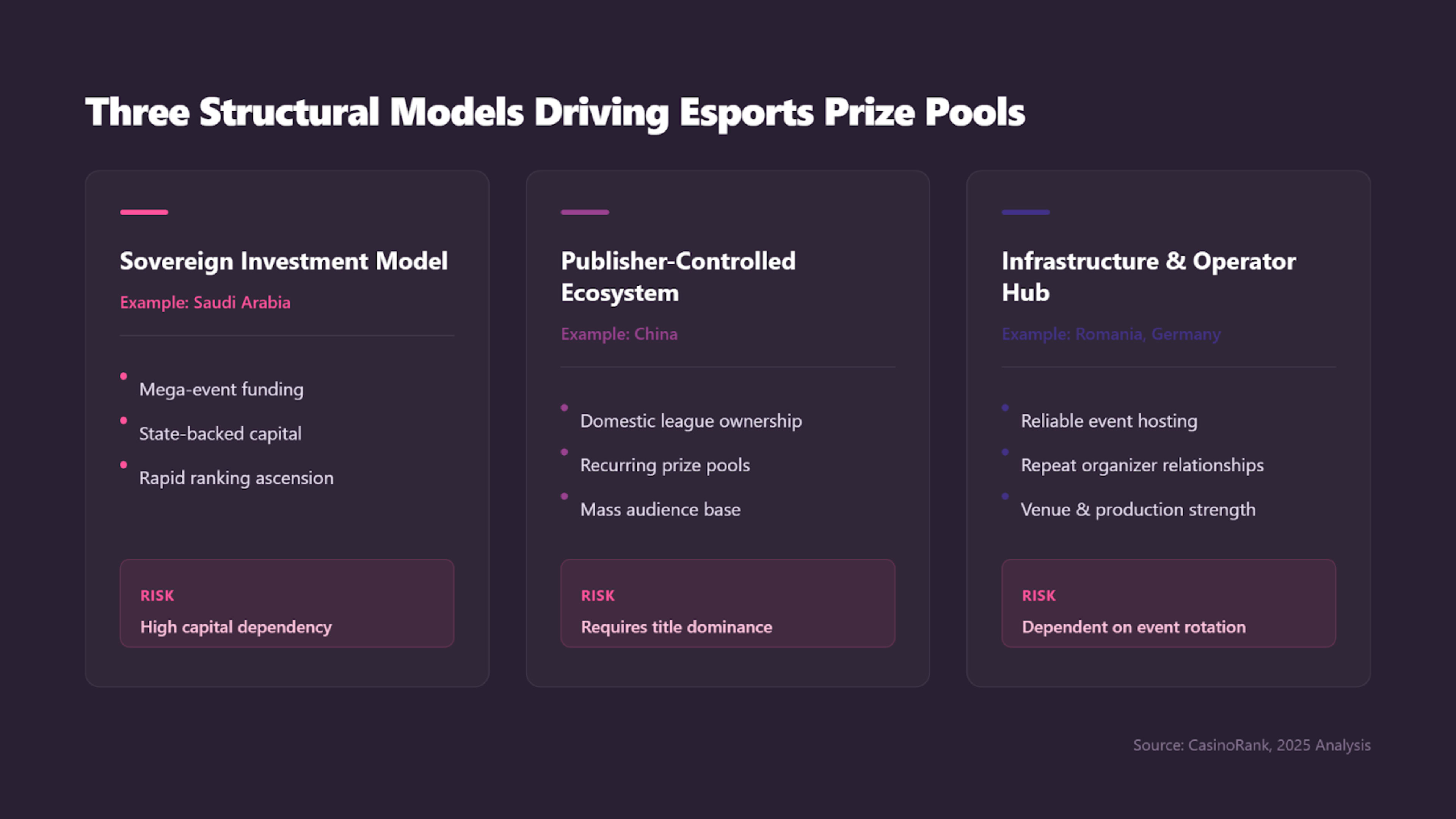

Across all ten countries, three structural patterns account for most of the variation in prize-money concentration.

Esports prize pools now cluster around three structural models: sovereign-backed mega-events, publisher-controlled ecosystems, and established infrastructure hubs.

Sovereign investment creates instant gravity.

Saudi Arabia is the obvious case, but the pattern extends further. When a government or state-adjacent entity decides to make esports a national priority and backs that decision with serious capital, the rankings respond quickly. The EWC circuit did not exist a few years ago. It now holds the number one position globally. This is the fastest route to the top of this table and also the most externally dependent, as it requires sustained political and financial commitment.

Publisher-controlled ecosystems reward scale

China's KPL demonstrates what happens when a publisher with a massive domestic audience decides to run a competitive league rather than license one out. The prize pool becomes a product of the ecosystem, not a prize attached to an external event. This model yields more stable, recurring contributions to the prize pool than sovereign investment, but it requires a title with genuine mass-market penetration to be effective. You cannot build a KPL equivalent around a game with a small player base.

Repeatable operator relationships build sustainable totals

Romania and Germany demonstrate that a country does not require sovereign investment or a dominant domestic publisher to reach the top ten. What it needs is a reliable event infrastructure and a track record that makes operators want to return. PGL keeps coming back to Bucharest. Valve brought TI to Hamburg. These relationships compound over time and yield more consistent results than one-off investments or single-title dependencies. We consider this the most underrecognized path in the ranking, and one country that warrants greater attention.

What the Global Numbers Tell Us

Zoom out, and the 2025 picture is one of measured growth. Total prize money exceeded $270 million across more than 10,500 tournaments, up 15.5% year-over-year. The growth is real, but it is also concentrated. The top ten countries account for more than half of all prize money globally, and within that group, the top three account for more than half again.

That concentration is worth watching. A market in which prize money increasingly pools around a small number of mega-events and dominant domestic ecosystems looks very different from a market in which growth is distributed more broadly. Whether the 2026 rankings show further concentration at the top or a wider spread will tell us something meaningful about where the industry is actually heading.

Looking Ahead

The 2025 data makes one thing fairly clear: the geography of esports prize money is now as much a policy and investment question as a competitive one. Countries seeking to attract significant prize pools have options, but these options require either capital, publisher relationships, or operational infrastructure that takes time to build.

Saudi Arabia has shown how fast the capital route can work. China demonstrates what the publisher route looks like at full scale. Romania and Germany exhibit a slower, steadier path of infrastructure development. Each model has a different risk profile, and 2026 will test all three as the event calendar takes shape and publisher priorities shift.